Father and daughter were reunited in the Afghan capital, Kabul, on Saturday. Until then, Gul only knew her from a photo. Gul was transferred to Guantanamo Bay in 2007 when his wife was pregnant. He was released after a US judge ruled for seven months that his detention was illegal and served no purpose.

This reduced the number of Afghan detainees at Guantanamo to just one man: Muhammad Rahim, 56. His chances of release are considerably less. US authorities consider him a “high quality” prisoner linked to al-Qaeda.

But according to his lawyers, the authorities are most concerned that Rahim will reveal details of how he was tortured. That this happened was already clear in 2012 in a US Senate report.

The other 34 detainees still held at Guantanamo are all of different nationalities. The camp once housed nearly 800 inmates. When he became president in 2009, Barack Obama promised to shut down the camp. This was never implemented, primarily due to opposition from Republicans in Congress.

Like many other detainees, Harun Gul, who is around 41, has been denied access to a lawyer for years. This happened only in 2016. The procedure to find out the reasons for his detention lasted six years. In the end, these reasons turned out not to be there.

Gul was not a member of Al-Qaida or the Taliban. In 2001, the year of the attacks in the United States, he was a member of the Hezb-i-Islami militia, which sometimes collaborated with Al-Qaeda. The facts regarding Gul’s personal involvement, if any, have been classified by the authorities.

Either way, Gul was a “very small fish”, writes Kate Clark of the Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN), who has followed the case for years. “It’s hard to understand why such a small player was brought to Guantanamo in the first place.” The charge against him was based on “rumors and evidence obtained by torture”. Gul was also frequently tortured.

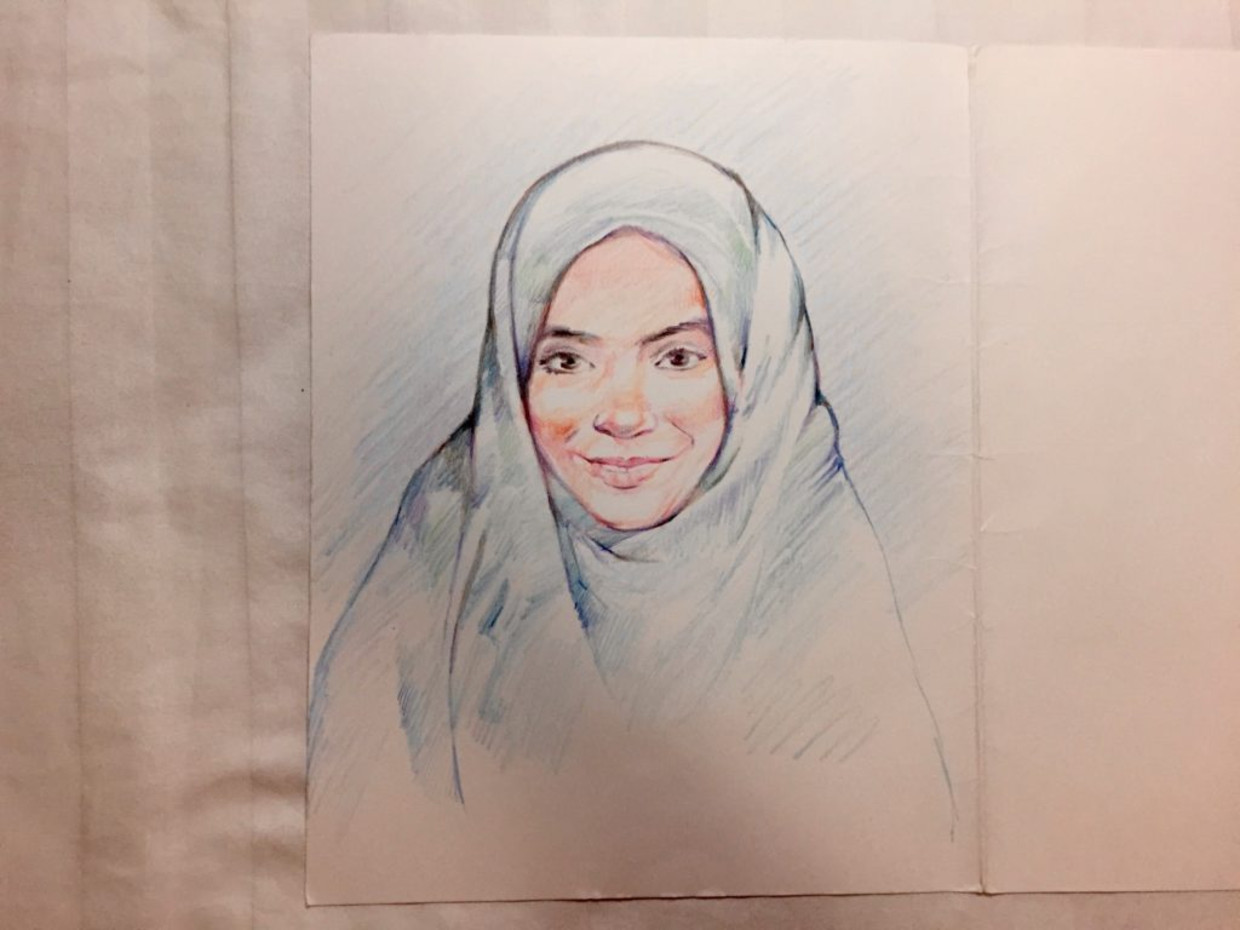

The Afghan belonged to the group of privileged prisoners authorized to draw and paint. Gul was the most prolific of the group. Besides portraits of his daughter, he mainly painted flowers, landscapes and the sea. The latter was remarkable, because as a resident of a country without a coast, he had never seen the sea. fabrics to prevent the detainees from having a view of the sea, which they always heard.

That only changed in 2014, Clark writes, when the canvases were removed for four days due to an approaching storm. “It was like a vacation,” Yemeni Mansoor al-Dayfi wrote in his diary. “Those who could see the sea kept staring at that big blue. In their drawings of the sea, they put their hopes, their pains and their dreams. The sea is freedom.

“Infuriatingly humble social media ninja. Devoted travel junkie. Student. Avid internet lover.”

DodoFinance Breaking News Made For You!

DodoFinance Breaking News Made For You!